I learned to only drop in if you can connect to another peak. Find peak after peak. I learned to stay high on the foil and carve around the top of the swell’s crest, almost as if falling off the backside of it. Looking around is key. To retrace yourself is to link back to the original piece of high water and ride it back downhill. There are so many factors that change the shape of a wave in the open water: depth, current, wind, inertia. To keep your eyes open as the ocean changes beneath your feet, then respond to it makes downwinding a transitive experience. It is a return to the hunter-gatherer instinct that is somewhere embedded in our DNA.

Rule #1: To downwind, you need to forget everything you know about wave riding.

It took me countless attempts. And every time I crashed into the cold pacific water and I ate another slice of humble pie, I was starting to build a mental map of how to do this new thing. My mind was in a panic and rushed to make sense of something my body couldn’t catch up with. I recommend taking breaks and puzzling it out. In his book ‘The Wisdom of Insecurity’, Alan Watts claims “the root of all our problems is our desire to hold onto things. Life is constantly flowing, and we must let it.”

Such is downwinding.

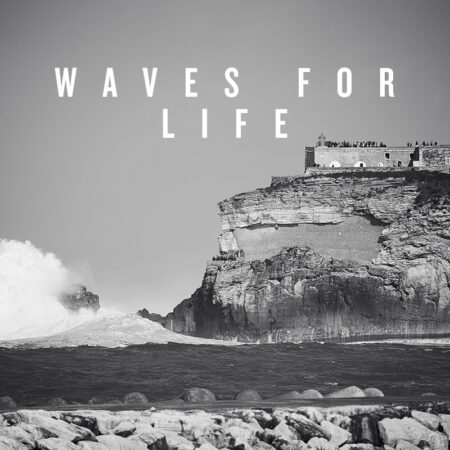

In May I flew to Oahu. The summer trades were wicking the rolling lumps of Pacific swell into a lather, which crested and collapsed like a parade of maniacal elephants that crashed against the cliffs of the southern coast. It was the heaviest sea state I’ve ever experienced and yet an average Hawaiian day. Gavin Ball whipped me in off a tow line from his ten-foot inflatable dinghy. I looked beyond the crestline to the backdrop of the island resting in idyllic sunlight. I pushed weight into my heels, carving and retracing my path to face two thousand miles of blue water stretching out toward Polynesia. The expanse of the open ocean and the energy of the swell shook every cell in my body. The adrenaline made my legs shiver.

Gavin and I switched and it was my turn to tow him up. He must have sensed I was a little leary to take the tiller of his 25hp Suzuki, which was smoking at the back, “I’ve taken this beast all the way to Molokai,” he reassured me. It was harder to drive the dinghy than the foil, but at least I got to watch Gavin link a few turns down the face of another marching elephant, as he disappeared leaving me to admire the brow of Diamond Head in the distance.

Faulty assumption #2: Downwinding is like surfing.

Downwinding is sailing at its core. Once you become competent at managing the flow of the foil beneath the water it works very efficiently. The foil will pop, drive and float. Then the main source of drag becomes your own body as it sails through space. A good downwinder is a lazy downwinder. Using the ocean’s power efficiently to connect one wave to another, but also take advantage of the wind’s power to get through the flatter sections. Gavin taught me this lesson as he masterfully carved towards and away from his island while he sought to gain or burn speed.

Rule #2: When you need speed let the wind push you, if you have speed connect to new ridgelines by riding crosswind.

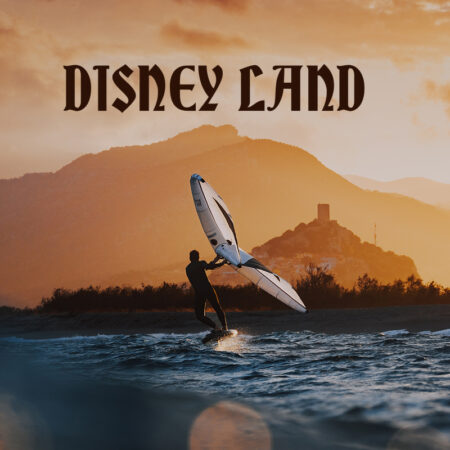

In November, the season's first Nor’easter pushed down the Florida peninsula. Quinn [Wilson], Nic Muller, Carlos Robles and I were frothing as we passed beneath the Bear Cut bridge in my 18ft boat. Once we got just offshore of Virginia Key, Carlos and Nic pumped up their wings and jumped in, foiling over the sandbar and into the swell off of Key Biscayne. Quinn and I drove further offshore. The swell was four feet at seven seconds, the wind 14 knots. We had about 30 minutes until dusk as the tropical sun sank beneath the horizon. I watched Quinn link 15 turns on one lump, as if he was charging through waist deep powder. “I felt like I could go forever!” Quinn said, grinning, as we traded helm and foil. It’s a ten-mile run from the Virginia Key to the southern tip of Key Biscayne. We reached the Bill Baggs lighthouse as the sun melted into the horizon above Key Largo.

Faulty assumption #3: What worked last session will work this session.

I was testing a smaller tail wing on this run, hoping to find more carve and top end. The foil’s sensitivity felt pitchy at first, and it took me several attempts to sort out my foot placement. I found a narrow stance and started paying attention to the glide I could get while favoring my backside. The wind’s direction was side-onshore, endless lefts. I could gauge a few snaps on my forehand crosswind before linking long carves on my backhand as I rebuilt speed dead downwind.

Rule #3: Continue to discover what will work for “this run”.

My boy Alan Watts writes, “…music is a delight because of its rhythm and flow, yet the moment you arrest the flow, prolong a note or chord beyond its time, the rhythm is destroyed. Because life is likewise a flowing process … to work against [it] is to work against life itself.”

Perhaps there’s something to that. Downwinding is jazz. It is improvisation. The landscape of the ocean, even one mile offshore, is a fickle foreign swirl. Unrestrained by a bordering coastline the windblown surface dances in a cacophony of swell, chop and spray belied by the ocean’s depth. Three miles out it becomes a rhythmic undulation. The sheer energy of that cosmic churn is a captivating phenomenon.

To downwind on a foil is to become a human tumbleweed. To position yourself in the tumult of the sea and let the path unfold before you. You only have two options: ride crosswind or downwind. It’s a beautiful exercise of acting within the present moment. And as you hunt for the next lump and milk it for everything you can, before turning toward the next, you string together the ride of your life. I think you owe it to yourself to try it.

Now subscribe to the world's best foiling magazine!

To get the latest premium features, tests, gear releases and the best photojournalism in the world of foiling, get yourself a print subscription today!